James Joyce and Belvedere College (“Blog Post IV”)

Did you know that James Joyce was educated at Belvedere College, the prestigious private school that hosts our English Summer Camp for Teenagers, for no less than five of what were arguably the most formative years of his life? Joyce — who would go on to become a world-famous novelist of the modernist avant-garde, making Belvedere College renowned worldwide through his autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) — entered Belvedere in 1893 at the tender age of 11 and proved himself to be a very bright pupil there right up until his departure upon graduation in 1898 at the hardy age of 16. In a previous blog post, we shed partial light on ISI’s unique relationship — as an English school in Dublin— to this stalwart literary figure; universally acclaimed as one of the most in influential writers of the 20th century. In this blog post, part “IV” of a very enlightening series of “V” (you can read part “III” here) we want to enlighten you further by focusing on the rich religious heritage of Belvedere College — the base of our English Summer Camp in Dublin — as well as Joyce’s place, as but one of many famous alumni, within and beyond it.

In 1898, James Joyce graduated from Belvedere College, S.J., Dublin: a private inner-city Catholic boys’ school under the trusteeship of the Society of Jesus (or Jesuits, as they are less formally known). He had been a student there for five years. Prior to this, notwithstanding a brief hiatus with the Christian Brothers, Joyce had been a student at Clongowes Wood, the Jesuit’s sister College in Salins, Co. Kildare. His Jesuit masters, “even when they had not attracted him, had seemed to him always intelligent and serious priests, . . . During all the years he had lived among them in Clongowes and in Belvedere . . . he had never heard from any of his masters a flippant word: it was they who had taught him christian doctrine and urged him to live a good life and, when he had fallen into grevious sin, it was they who had led him back to grace” (James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man).

Joyce’s debt to his Jesuit education, both as a writer and a person, has been sufficiently explored in disquisitions on his life and works. Indeed, writing about his time at Belvedere College alone, Constantin Curran, a close friend of Joyce and a character in A Portrait, said that in so far “as teaching can make a writer, it was [here] that the neophyte learned his art . . .” “During those five years at Belvedere,” Kevin Sullivan writes, “Joyce showed himself a serious and ambitious student, submissive to the intellectual discipline of the Jesuits and obedient to their moral and religious counsels.” “They taught me how to order and to judge,” Joyce himself later remarked. To which his most esteemed “biografiend” Richard Ellmann would add that the Jesuits endowed him with “the ritual and moral codes which, in all his rebellion, he would never cease to Tind fascinating. For Joyce’s books could not exist without Catholicism as panoply or as theme.”

Rather than suggest fresh perspectives for this discussion here, this post and the previous one, follow Leo M. Manglaviti, S.J., in revisiting a living artefact of Joyce’s Jesuit education: “Belvedere House, the Jesuit community residence at Joyce’s Dublin alma matter.” With Manglaviti, we are curious to know what exactly Joyce saw each day during the years he spent in Great Denmark Street?

As mentioned in our previous post, Manglaviti claims that “students in Joyce’s time [actually] saw very little of the Jesuit residence itself, except for the imposing facade on Great Denmark Street,” pictured above (Fig. 3). “Designed by Robert West in 1786 for George Augustus Rochfort, the 2nd Earl of Belvedere, Belvedere House, despite replacement brick walls and timber sash windows, retains its original appearance and detailing complete with a very fine Doric door-case. Having also one of the finest eighteenth-century interiors in Dublin with extensive neo-Classical plasterwork by Michael Stapleton, Belvedere House provides one of the most dramatic vistas as it terminates the north end of North Great George’s Street, adding to the overall impression of this Georgian mansion. The late twentieth-century wings mimic the architecture of the earlier building and complement its setting (National Built Heritage Service, Ireland).” Manglaviti’s “Sticking to the Jesuits: Revisiting Belvedere House” (2000) follows Bruce Bradley’s James Joyce’s Schooldays (1982) in noting how this “house, which was acquired by the [Jesuits] in 1841, was no longer in use for school matters in the 1890s, since by that time all student activities were centered in the adjoining buildings.” Accordingly, a student of Belvedere College would, in Joyce’s day, only have seen the stunning interiors of Belvedere House itself through a private invitation from one of their Jesuit superiors — as this was their living quarters — and there is no extant evidence to suggest the young Joyce was ever accorded one. For Bradley, “[t]his accounts for Joyce’s ‘surprising failure’ to have his alterego, Stephen, in A Portrait make ‘any mention at all of the magnificent interior decoration’ of the main hall, stairway, or rooms in the classical style dedicated to Apollo, Venus, and Diana . . .”

It is doubtful then, in following Manglaviti’s account, that Joyce ever saw “the ornate ceilings and the elaborately decorated rooms of Belvedere House.” When the young Joyce entered Belvedere College in 1893, “only the Jesuits living there could enjoy the splendor of what was then solely a residence for the school faculty.” However, as Manglaviti notes, in A Portrait Joyce does depict his literary alter-ego Stephen visiting the Rector — though he remains nameless in the context of this oblique autobiographical novel, this was Fr William Henry, S.J. — about pursuing a Jesuit vocation. Their meeting takes place in the “college parlour,” which Manglaviti, in following Bradley, suggests would have been just off the entrance hallway pictured above (Fig. 2). “As Bradley reconstructs the scene when plays were performed, the audience would have entered from the street and passed through this hallway to the rear door of Belvedere house for access to the theatre in the quadrangle. After his interview with the rector, Stephen exited the house through the nearby ‘heavy hall door’ [Fig. 1 above], stepping into ‘the caress of mild evening air’ (P 160) of Great Denmark Street [Fig. 5. below]. He, like Joyce, would have seen only the hallway leading from entrance to rear door” (Manglaviti, “Revisiting Belvedere House”).

While the hallway leading from the entrance is itself impressive (Fig. 2 above), the ground floor rooms of Belvedere House were only ever intended for everyday and business use and are therefore minimally ornamented, as we can see in the picture below (Fig. 6); which also contains a close-up shot of Joyce’s name in gold lettering on a wooden plaque commemorating, in chronological order, the various prefects of the Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Belvedere College: a devotional Roman Catholic Marian society, which a thirteen-year-old Joyce became a member of on December 7th 1895 before assuming the honorary position of being the Sodality’s Prefect or “head” from 1896-98.

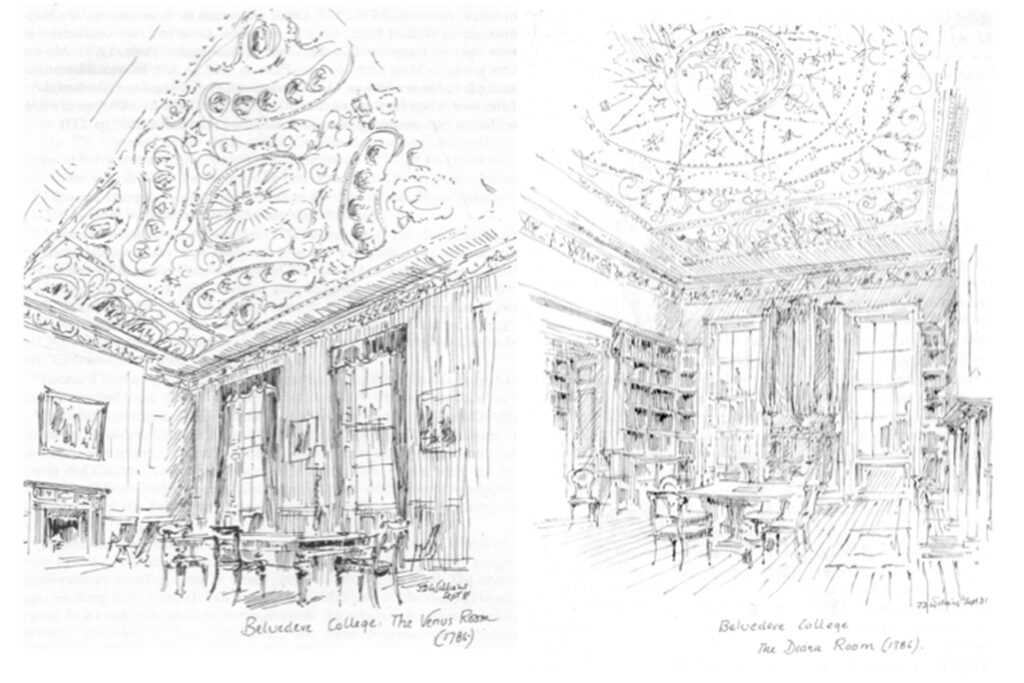

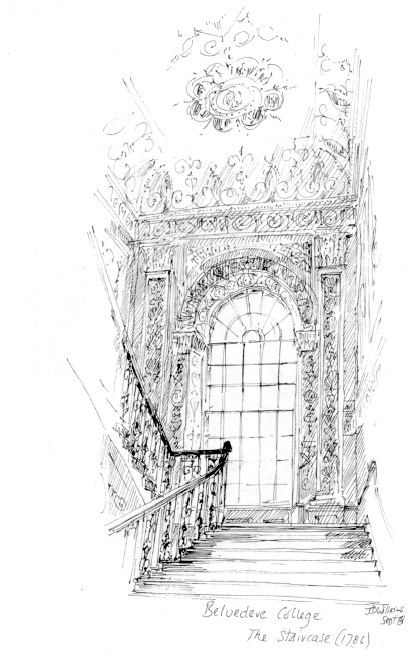

So, as mentioned, while the hallway leading from the entrance to the rear door on the ground floor of Belvedere House is itself impressive, this area was only ever intended for diurnal business purposes and as a result is minimally ornamented — accounting for Joyce’s “surprising failure” in A Portrait to have his literary alter-ego Stephen make any mention whatsoever of Belvedere’s magnificent interiors. However, as one ascends the grand stairway of Belvedere House they encounter incredible stucco-work depicting scenes from Greek and Roman mythology (Fig. 7, below). On the half-landing, the Bacchanalia is celebrated. The left panel depicts Bacchus with his thyrsis and staff, the right panel is Ceres with her cornucopia. The central oval shows Cupid being demoted by the three Graces. The arched window is ornamented with symbols of the authority of ancient Rome. One could go on, . . .

Manglaviti — whose account is replete with illustrations by J.D. Williams, which appeared in the Dublin Historical Record in 1953 (Figs. 4 and 8) — states that in order to fully appreciate the place of Belvedere House in Joyce’s school days and the effect it had upon his Tiction, it is necessary to review the troubling and somewhat haunting history of the house itself, now in its fourth century. In the first of this series of blog posts, we did just that — relaying the scandalous case of Mary Rochfort, first Countess of Belvedere, who languished under house arrest, having been accused by her husband, Robert Rochfort, first Earl of Belvedere, of an adulterous liaison with his brother, Arthur. As stated there, Lady Belvedere was imprisoned by her cruel husband in Gaulstown House in Co. Westmeath for the best part of thirty years. While it is doubtful that she ever even saw Belvedere House, which was constructed by her son George, erroneous legends abound that her ghost haunts the house; legends fuelled by the assumption that it was in this house that she was in fact imprisoned. Indeed, in ユリシーズ, Joyce has Father John Conmee, S.J., suggest that a “book that might be written about jesuit houses and of Mary Rochfort” would examine the truth of this Gothic fable. “In any event,” as Manglaviti attests, “Belvedere House was certainly in the Dublin consciousness around 1900 as having rather scandalous associations, and in ユリシーズ Joyce exploits the story of adultery and its sensational, though vague, details.”

It is certainly possible that Mary Rochfort, Countess of Belvedere, frequented Belvedere House while it was under construction, but it is highly unlikely that she ever lived there. (Nevertheless, as Manglaviti reminds us, “the facts are uncertain.”) By all accounts, the house was completed and occupied in 1786 — a letter from Charles Doyle, S.J., to Joyce himself states as much, while Joyce’s biographer, Richard Ellmann, merely says it was completed in 1785. This date of completion is supported by Belvedere art teacher Terry McMullen, who crafted two metal plaques that were mounted at opposite sides of the rear entrance during the 1980s. These read: “Belvedere House 1785” and “Jesuit Residence 1841.” Bruce Bradley, S.J., the Jesuitical authority on Joyce’s school days, brings “the vagaries of history together in a brief essay in the college annual, The Belvederian 1981.” As Manglaviti states, it is worth quoting in full:

Having succeeded his father the previous year and released his mother from captivity in Westmeath (she went on a visit to Italy and became a Catholic), George Rochfort, second Earl of Belvedere, married and began building Belvedere House in what was then Gardiner’s Row (the name “Great Denmark St” dates only from 1792), a little further south of the Poor Clare’s chapel. The building, designed and decorated by Michael Stapleton and with mantelpiece [sic] ornamentation by the Italian Bossi, was completed at a cost of £24,000, about 1786. It possesses what Desmond Guinness calls “the Tinest, neo-Classical plasterwork interior in Dublin” and is one of the most distinguished houses of its period and style in the city.

According to Bradley in Schooldays, to this day, Belvedere House has remained “virtually unchanged from the time of Joyce” with the exception of some modifications to the exterior.

Did you know that it was during his time at Belvedere College — in being assigned an English composition topic “My Favourite Hero” — that Joyce Tirst read Charles Lamb’s The Adventures of Ulysses (1808): the book which would inspire the outline for his world-famous novel?

Read all about it in the final instalment of this series of blog posts!