Here at ISI Dublin, we pride ourselves on having — over and above all of the English Language Schools in Ireland — a deep and meaningful connection to the Irish writer James Joyce. Not only did Joyce regard the Chapter House adjoining our Meeting House Lane campus as “the most historic spot in all Dublin,” but he himself was educated at Belvedere College, the prestigious inner-city school that hosts our Summer Camp for Teenagers. Universally acclaimed as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, Joyce is most famous for his novel ユリシーズ (1922), in which he makes the above, remarkable reference to our Meeting House Lane campus. However, in unearthing Joyce’s influences through this series of blogposts, we would rather not merely focus on Ulysses, but extend our academic reach to his early childhood and an abiding influence on his last and undisputedly most baffling work, Finnegans Wake (1939).

II: Astraphobia

When Joyce was five years old, his family moved to a house in Bray, Co. Wicklow, because his father, John Stanislaus Joyce, wanted to be further away from his in-laws and closer to the sea — so close, in fact, that their residence at 1 Martello Terrace occasionally got flooded. John F. Finerty’s photograph below, which was taken in the late 1890s, “shows the seawall promenade that runs toward Bray Head along a 1.6 km walkable beach.” Joyce’s younger brother, Stanislaus, “mentions the view of it from the Joyces’ house very near the coast on Martello Terrace: “‘From our windows,’” he says, “‘we had a long view of the Esplanade, which stretched along the sea-front half the way to Bray Head’ (My Brother’s Keeper, 4).” As John Hunt from The Joyce Project has noted: “This elegant mile-long promenade was built during the Victorian era, at a time when moneyed middle-class Dubliners were moving to Bray to escape the press of city life while remaining within commuting distance. The extension of the Dublin and Kingstown Railway to the town in 1854 transformed Bray into a comfortable suburban resort destination” (2017).

While living in Bray (1887-1892) the Joyce family were joined by a relative — one Dante O’Riordain in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man [1916]) — who became the children’s governess. Both this relative and Joyce’s Bray home are represented in A Portrait’s spectacular Christmas dinner scene, which sees Simon Dedalus, representative of Joyce’s father, crossing swords with Dante over the tragic death of Charles Stewart Parnell: Ireland’s “uncrowned king.”

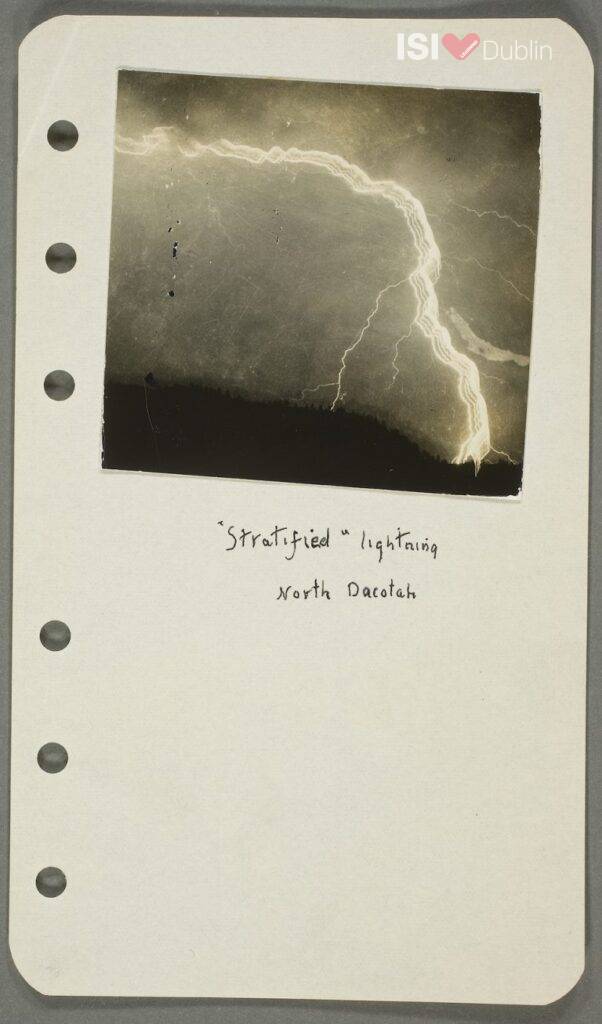

During her time as his governess, this staunch, unflinching Catholic woman taught the young Joyce to bless himself and pray every time there was a thunderstorm. Having made the sign of the cross upon his body, he would ritually say: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, from a sudden and unprovided for death, deliver us, O Lord.” Apparently, as a result of this morbid observance, and the terror with which it was rife, Joyce suffered from astraphobia — an abnormal fear of thunder and lightning — for the rest of his life.

In keeping with his quasi-autobiographical fashion, thunder and lightning would occur quite frequently in Joyce’s novels, usually in conjunction with death and the colour black. For instance, thunder and lightning play a prominent role in Finnegans Wake (1939), which is punctuated by ten instances of thunderclaps, each consisting of word combinations of 100 letters, and in one case, 101 characters. These so-called “thunderwords” incorporate words from many languages other than English and have multiple meanings. Of the ten thunderwords that appear in Finnegans Wake, we encounter the following on the first page:

bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!

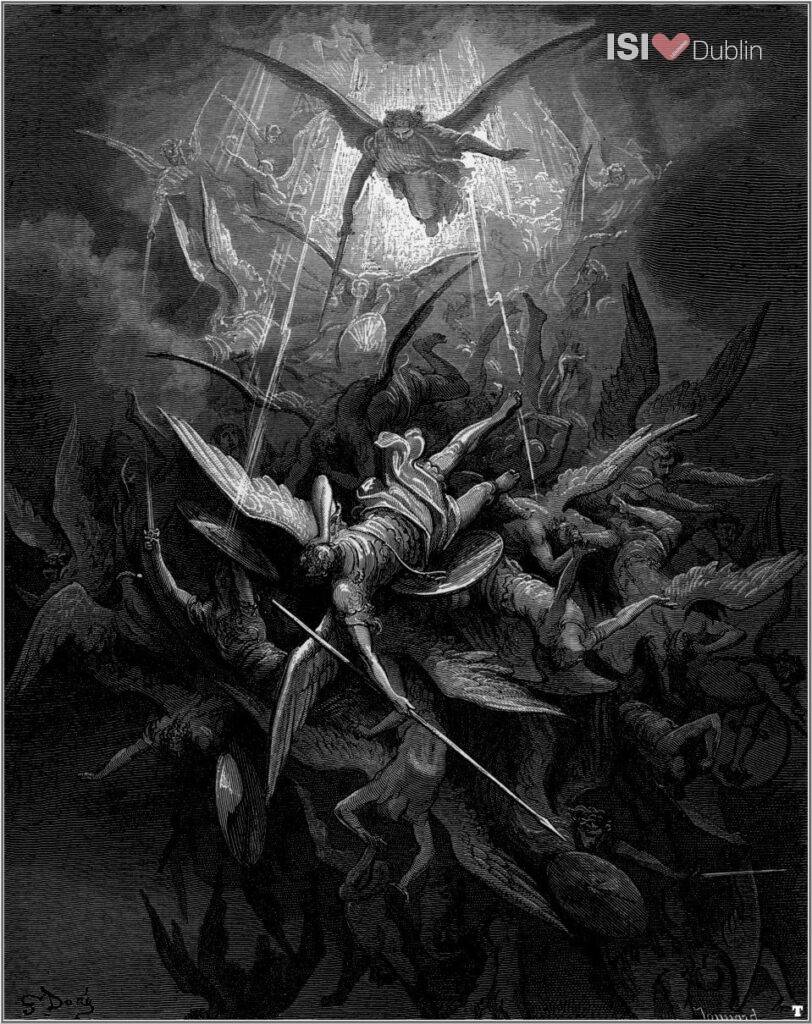

While looking like absolute nonsense, this thunderword is actually comprised of the word “thunder” in various languages. True to the style of the Wake, it is a play on Gargarahat, the Hindi word for thunder, for instance, immediately followed by a play on kaminari, which is thunder in Japanese. One could go on. More importantly to note though, is the fact that this thunderword is a skittish statement of one of Joyce’s major preoccupations — touched upon in our last correspondence — the thunderous sound of the downfall of man; the Babelian rumble that follows Lucifer’s “fall like lightning from heaven” (Luke 10:18).

As mentioned previously, sin was one of Joyce’s earliest and most enduring obsessions. He seems to have had an innate realisation that the most important dramatic role was that of the Tempter, and embodying this role became his lifelong endeavour. In 1902, the author and critic George Russell proffered: “There is a young boy named Joyce who may do something. He is proud as Lucifer.” (For his part, in Finnegans Wake Joyce would refer to himself as Mr Tellibly Divilcult.) Lucifer — “bearer of light, or morning star” — is also invoked in the very name Joyce gave to his daughter, Lucia, which, in Italian, literally means “Light.”

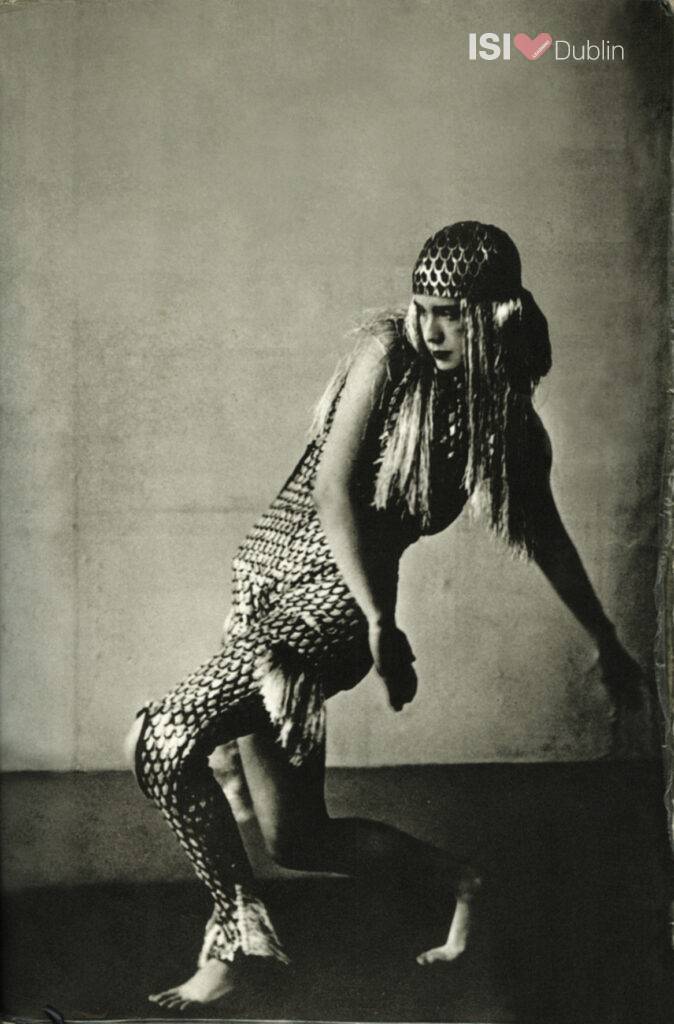

Born in Trieste, Italy, in 1907, Lucia was the second of Joyce’s children with lifelong companion Nora Barnacle. From a very young age, Lucia began training as a professional dancer. She is said to have had great talent as a ballerina and choreographer. She studied in several noteworthy academies and worked with some of the most experimental and avant-garde groups in early 20th century Europe. Following a performance at the Vieux-Colombier theatre, the Paris Times wrote of her: “Lucia Joyce is her father’s daughter. She has James Joyce’s enthusiasm, energy, and a not-yet-determined amount of his genius. When she reaches her full capacity for rhythmic dancing, James Joyce may yet be known as his daughter’s father” (Carol Schloss [2003] Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake).

However, from a young age Lucia had also begun to display neurotic traits, completely unpredictable behaviour, which seems to have reached an apogee in the 1930s, a period of time during which she was amorously involved with her father’s apprentice, Samuel Beckett; then junior lecturer in English at the École normal supérieure in Paris. In May of 1930, while her parents were away in Zurich, Lucia invited Beckett to dinner in the hope of pressing him “into some kind of declaration,” but Beckett firmly and unequivocally rejected her— stating that he was only interested in her father and his writing.

Further rejections followed in the same year, and from this unfortunate streak of events, Lucia allegedly emerged a violent, abject, and sexually promiscuous individual. The veritable straw that broke the camel’s back, so to speak, occurred on her father’s fiftieth birthday, when Lucia threw a chair at her mother, after which her older brother, Giorgio, admitted her to a psychiatric institute. Throughout this period Joyce was writing Work in Progress, which would eventually become his last novel, Finnegans Wake — a book many biographers believe was inspired, with both trepidation and elucidation, by Lucia herself.

Belisha beacon, beckon bright! Usherette, unmesh us! . . . Where flash becomes word.

— James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Read all about it in our next blog post on ISI and James Joyce: Influences (III)!