Did you know that when you choose to live and study in Dublin, you are choosing one of forty-two cities spanning thirty-two countries and six continents that has the prestigious designation of UNESCO City of Literature? Following on from our previous blog post on great Dublin Bookshops, we thought we should slow down and savour ISI’s unique relationship — as an English school in Dublin — to Ireland’s rich literary heritage.

Ireland has unfailingly produced major literary figures whose achievements, across all literary genres, have been universally acclaimed. Often noted by scholars and academics, it is more than somewhat ironic that a great deal of the canon of “English” literature has been produced by Irish and Anglo-Irish writers: Sheridan Le Fanu, Bram Stoker, William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory, Sean O’Casey, George Bernard Shaw, J.M. Synge, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Brendan Behan, and Mary Lavin, . . . to cite just a few amongst them!

Many of theses writers are native to, or connected with, Dublin city. In fact, some of the most famous names in the history of English literature and drama were born within a few square miles of Dublin’s city centre: Wilde, Synge, O’Casey, Joyce, Yeats, Shaw, and Beckett. And the tradition continues today with Dublin writers such as Roddy Doyle, Joseph O’Connor, and Emmet Kirwan penning critically acclaimed plays and international bestsellers.

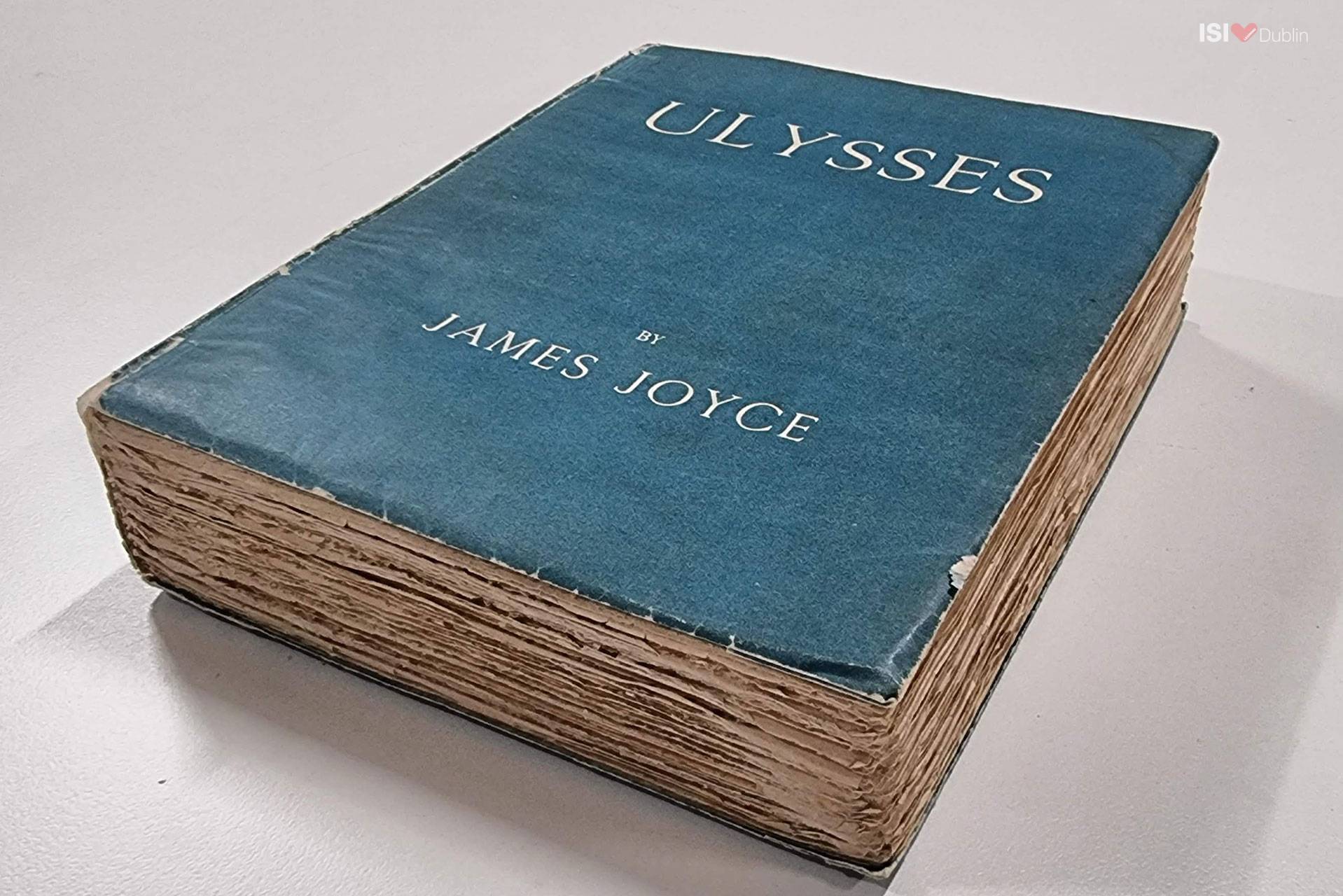

Here, at ISI, we have a very special, indeed unique, relationship to James Joyce. Joyce is a peerless Irish writer and a central figure in the history of the novel. He introduced a new technique which allowed writers to craft novels that read like the protagonist’s stream of consciousness. His principal work, Ulysses (1922), is widely regarded as one of the greatest works of literary modernity. Named after the most dramatic adventure story handed down to Western civilisation by the ancient Greeks, it relays the wanderings of Leopold Bloom as he traverses the streets of Dublin city over the course of one day in June 1904. We see him cooking breakfast, conversing with his cat, attending a funeral, preparing to take a bath, going to work, having lunch, listening to someone sing, having various conversations, drinking coffee and cocoa, worrying about his wife and daughter, befriending a young school teacher, . . . and so on. Unlike the hero of Homer’s odyssey, the major character of Joyce’s novel is not a warrior king, but a fairly flawed, rather foolish but kind individual who is representative of our average, unimpressive everyday selves.

Against the false heroics of World War 1, Joyce’s Ulysses set out to restore the dignity of what Declan Kibberd has termed “the middle range of human experience.” In his commitment to this idea of the grandeur of ordinary life, and in his determination to portray what really goes on through our minds — moment by moment, in addition to his perseverance in presenting on the page what language actually sounds like in our heads, Joyce remains one of most revered writers in the English language.

Employing Cubist techniques popular with painters at the time that he was writing, one of the most accomplished “episodes” in Ulysses is “Wandering Rocks.” Cut up into nineteen sections, some consider this episode a guide or map to the book as a whole — with each section corresponding to one or other of the episodes comprising the novel and a number of which even describe the same events from a different angle. It is here, in the eight section, that Joyce has a character called Ned Lambert tell one Reverend Hugh C. Love that the Chapter House adjoining our ISI Meetinghouse Lane campus is “the most historic spot in all Dublin.”

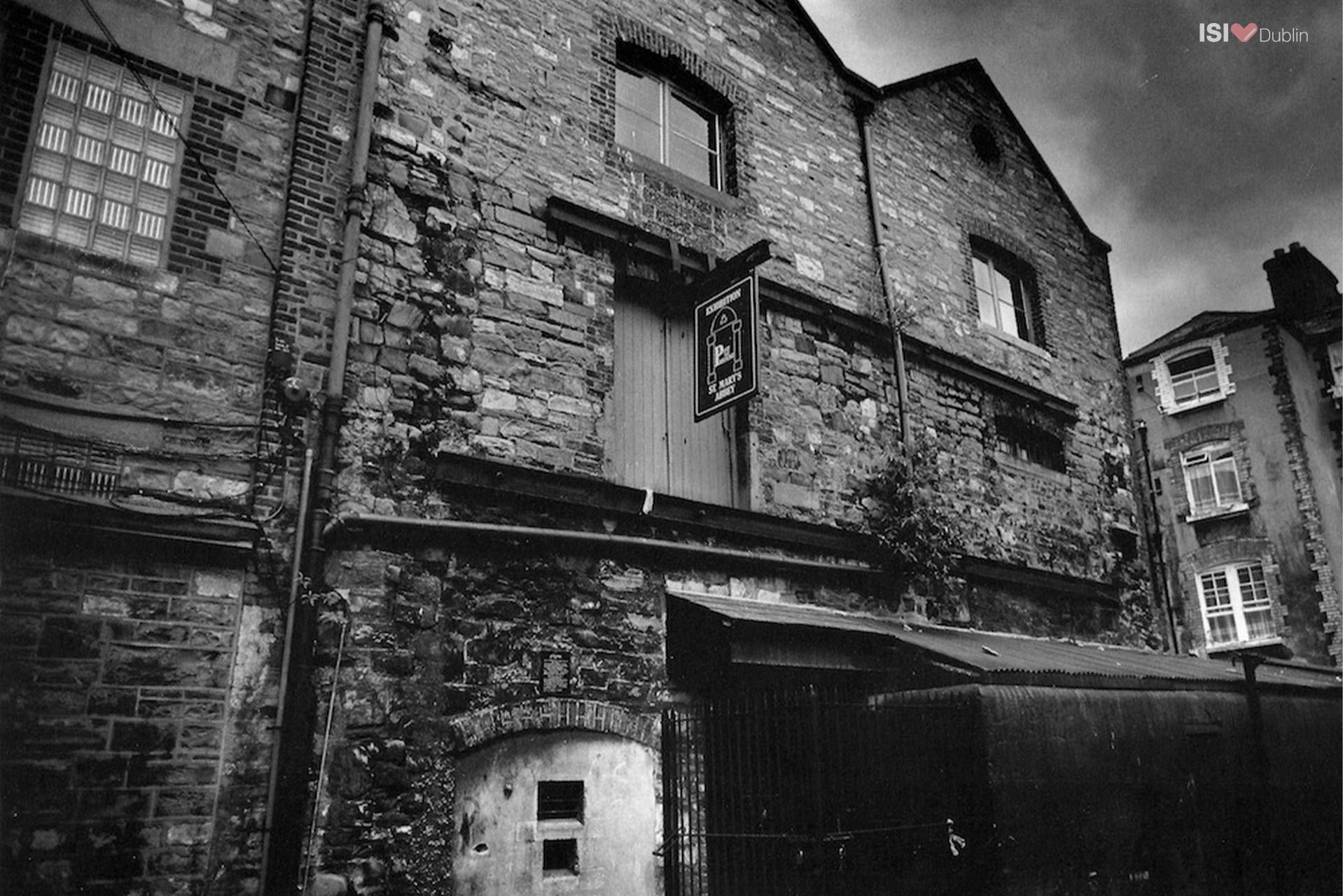

The very building accommodating our Meetinghouse Lane campus is the only remaining building of what was once an exceptionally large complex housing the wealthiest abbey in Ireland, St. Mary’s Abbey. According to the Annals of the Four Masters, the abbey was founded in 846 by the Irish king Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid. It was originally Benedictine, but circa 1140 was given over to the Congregation of Savigny and what would then become a Cistercian abbey, the remains of which were declared a national monument in 1941. Despite this noble building having descended to serving as a warehouse for a seed business in 1904 — the year that Ulysses is set — the Chapter House adjoining our school was once a lofty space where all the members of the abbey would meet to conduct their business. Situated just below our first-floor reception, it is a beautiful, arresting space with a groined store roof commanding attention.

In medieval times, it was not uncommon for monarchs and other nobles to sequestrate such spaces for affairs of state, and the Chapter House at St. Mary’s Abbey was no exception. In Joyce’s Ulysses, the Reverend Hugh C. Love has come to visit it because of his interest in the history of the Irish aristocracy, and Ned Lambert very proudly describes it as “the most historic spot in all Dublin” — for it was indeed here that bore witness to the first significant Irish insurrection against the English when “[S]ilken Thomas [Earl of Kildare] proclaimed himself a rebel in 1534.”

In Joyce’s Ulysses, the Reverend Love intends to make a return visit to photograph the Chapter House and Ned Lambert suggests some “points of vantage” where a camera could be placed. Unfortunately, as Ulysses is set over the course of just one day — June 16 1904 — we never get to see this task underway. Luckily for us however, it is a task that has since been taken up and admirably accomplished by the Irish photographer Andy Sheridan, as evinced in the image below — courtesy of the wonderfully informative Joyce Project.

Here, at ISI, we are so grateful to live and learn every day amidst the alluring ambience of the abbey and the ever-present spirit of Dublin’s greatest writer, James Joyce . . .

Did you know that Joyce was himself an English language teacher? Did you know that he was educated by Jesuits as a junior at the very school here in Dublin city-centre where we host our ISI Gençler için İngilizce Yaz Kampı? Read all about it in our next blog post!