Here at ISI Dublin, we pride ourselves on having — over and above all of the English Language Schools in Ireland — a deep and meaningful connection to the Irish writer James Joyce. Not only did Joyce regard the Chapter House adjoining our Meeting House Lane campus as “the most historic spot in all Dublin,” but he himself was educated at Belvedere College, the prestigious inner-city school that hosts our Summer Camp for Teenagers. Universally acclaimed as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, Joyce is most famous for his novel Ulysses (1922). Heavily influenced by Homer’s Odyssey, the narrative explores themes of identity, heroism, and the art of everyday living. Its stream-of-consciousness technique and labyrinthine structure make this novel one of the most rewarding yet complex works of literature. But did you know that you don’t need to be a C1-C2 student, let alone an English professor, to enjoy the fruits of Joyce’s literary labour? In this blog post, the first of a series exploring his influences, we want to introduce you to one of his lesser known but more accessible literary works, “The Cat and the Devil.”

I. Temperament

“A work of art,” Émile Zola once said, “is a corner of creation seen through a temperament.”

In My Brother’s Keeper (1964), Stanislaus Joyce’s earliest recollection of his brother is of a dramatic performance of the story of Adam and Eve, organised for the benefit of his parents and the nursemaid, “in which Joyce was the devil.” “What I remember indistinctly is my brother wriggling across the floor with a long tail probably made of a rolled-up sheet of paper or towel.”

(Joyce, Stanislaus, My Brother’s Keeper: James Joyce’s Early Years, ed. Richard Ellmann [New York: McGraw Hill, 1964], 3.)

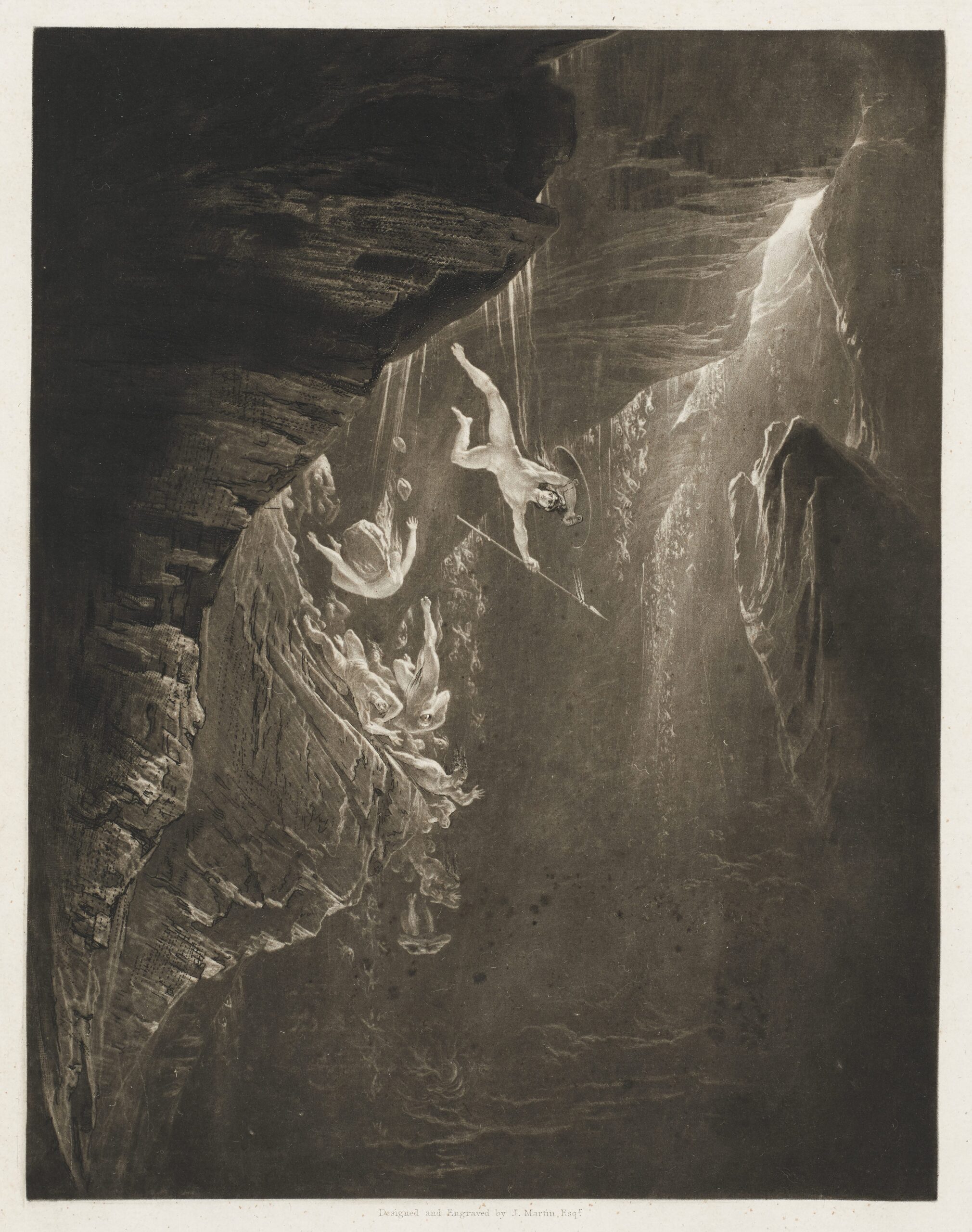

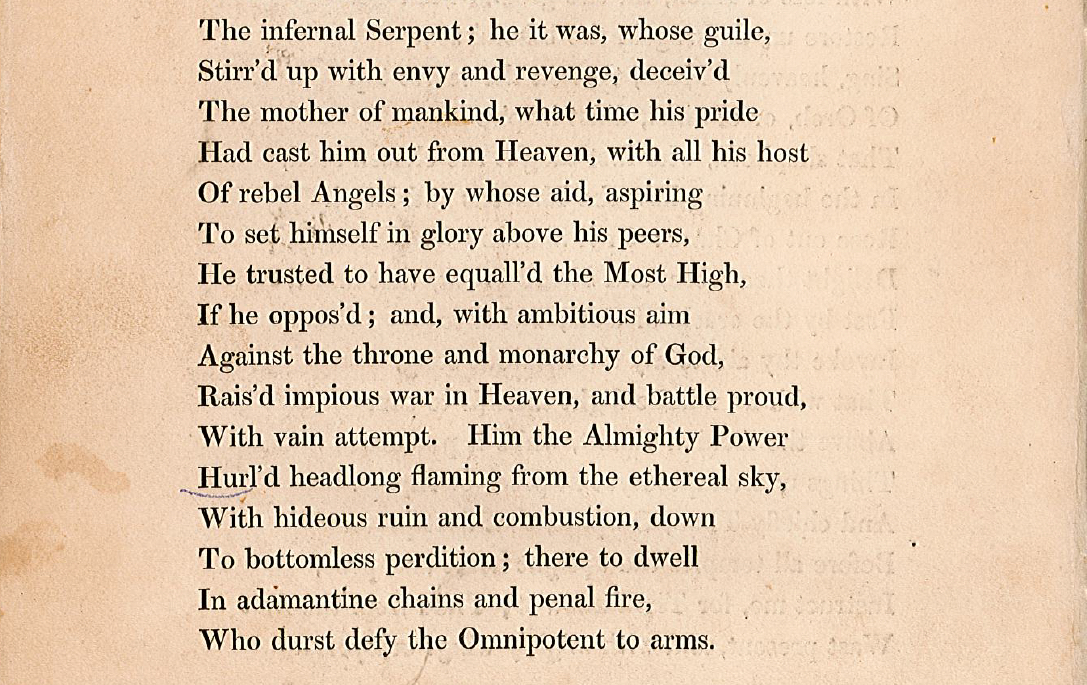

James Joyce’s first recorded memory is thus artistic, not only performative but rebellious, in which he, cast “as the Serpent, or Satan in the Serpent,” embodied: “Man’s disobedience, and the loss thereupon of Paradise wherein he was placed.”

(Milton, John, The Paradise Lost, Illustrations by John Martin [London: Charles Tilt, 1833], i.)

Ten years after his untimely death in 1941, Brian Nolan (aka Flann O’Brien —another of Ireland’s great writers) confirmed: “James Joyce was an artist. He said so himself. His was a case of Ars gratia Artist [Art for Art’s Sake]. He declared that he would pursue his artistic mission even if the penalty was as long as eternity itself.”

(Nolan, Brian, “An Editorial Note: A Bash in the Tunnel,” in Envoy: An Irish Review of Literature and Art, ed. John Ryan [Dublin: Envoy Publishing Ltd., 1951]: 5-11; 5.)

A little later on in the same piece of writing, Nolan reckons:

Joyce went further than Satan in rebellion.

The histrionic Satanic temperament ascribed to Joyce by Nolan is once again traced back to his boyhood by Richard Ellmann who, in his biography of the artist, notes how “Satan was useful in another way” according to an amorous interest from Joyce’s childhood days:

When James wished to punish one of his brothers or sisters for misconduct, he forced the offending child to the ground, placed a red wheelbarrow over him, donned a red stockingcap, and made grisly sounds to indicate that he was burning the malefactor in hellfire.

(Ellmann, Richard, James Joyce [New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982], 26.)

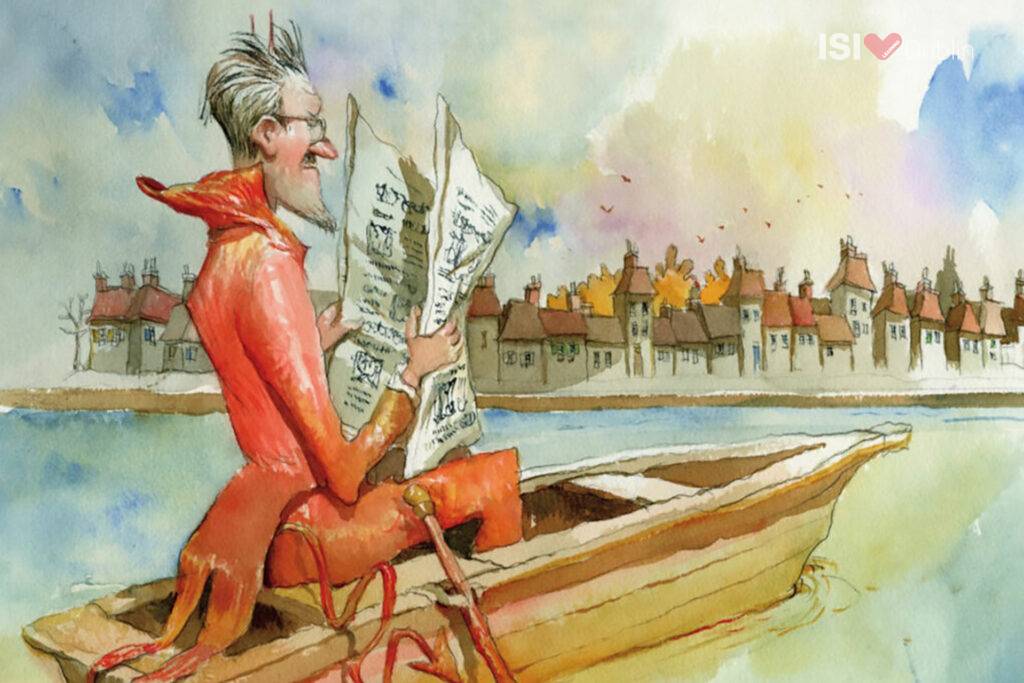

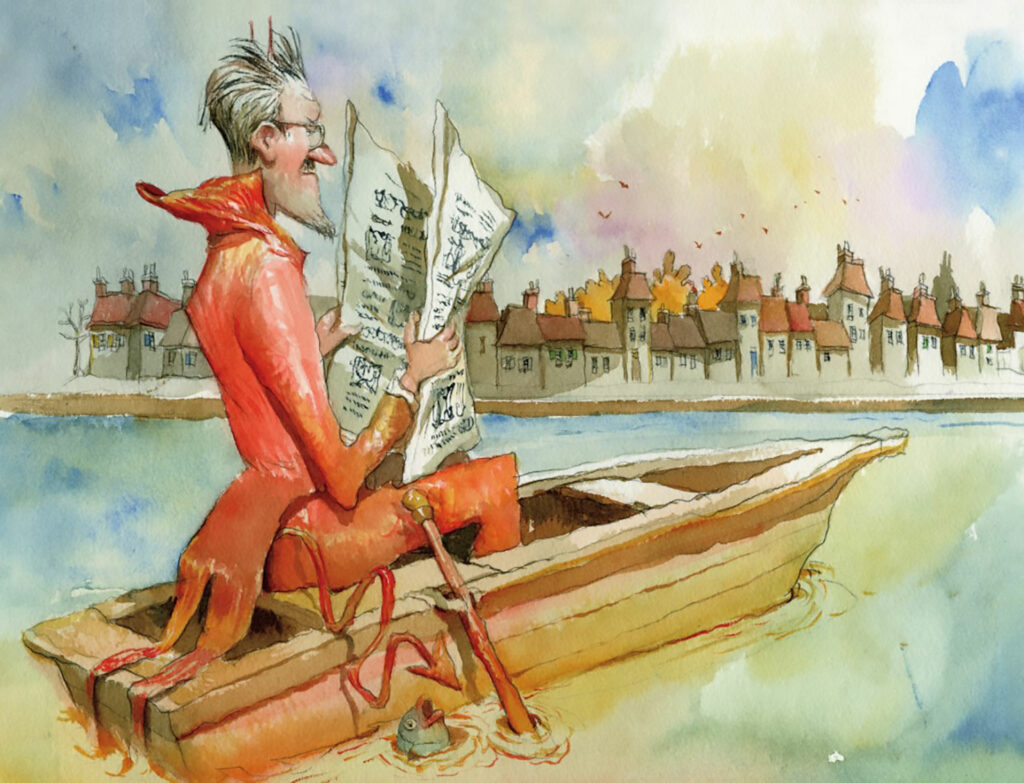

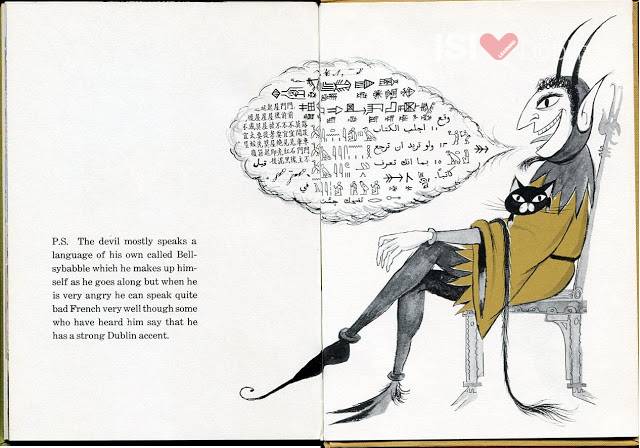

Little wonder, then, perhaps, that thirty years later in Zurich, when a man of growing international remark, Joyce was dubbed “Herr Satan” by a landlady “because of his pointed beard and sinewy walk”(ibid.) — which is exactly how we find him brought to life in various illustrated versions of The Cat and the Devil: Joyce’s retelling of a French Folk tale concerning the titular town of Beaugency on the Loire river.

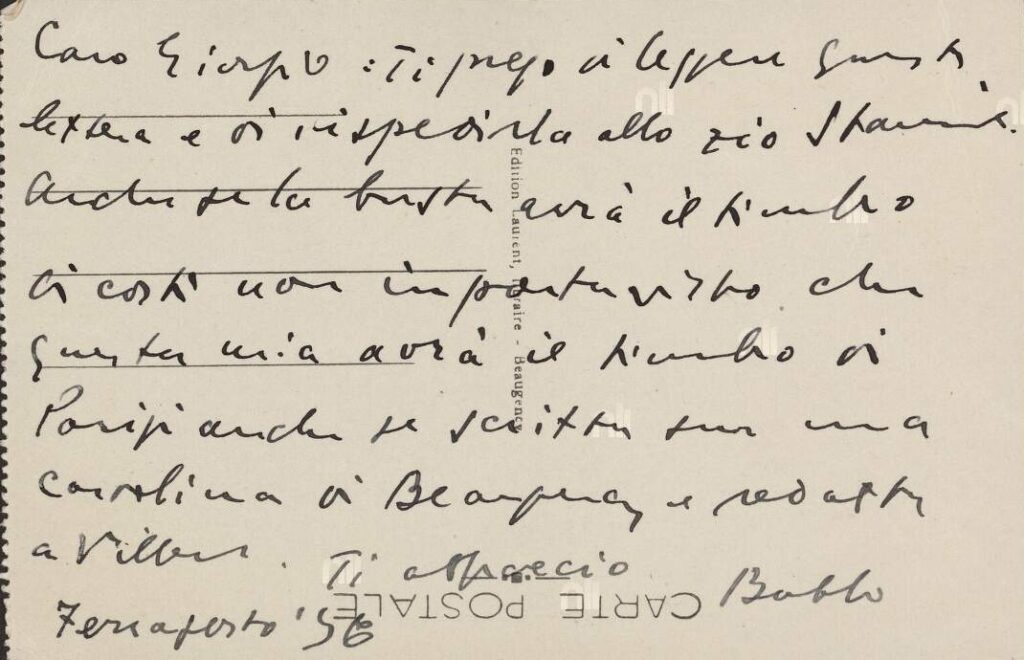

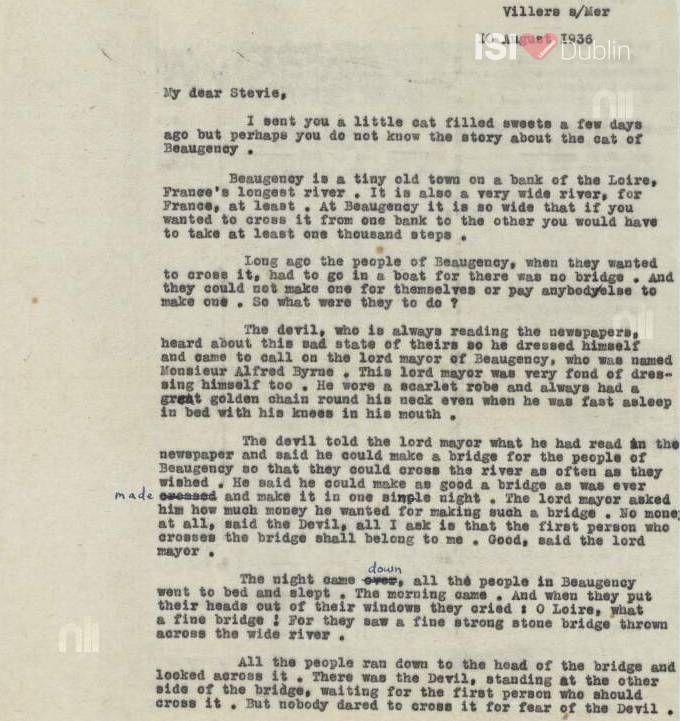

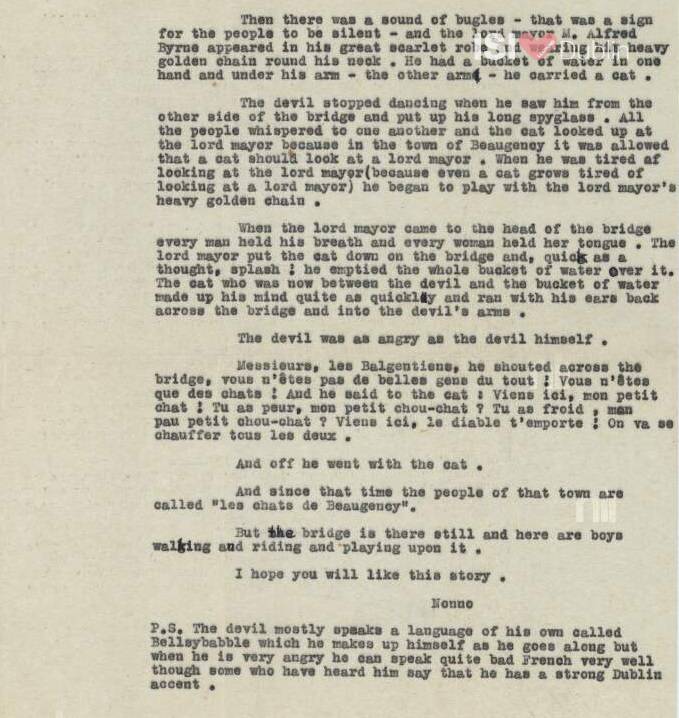

It is believed that Joyce visited Beaugency at least twice during his life — once in August 1936 and again in July 1937. The story of “The Cat and the Devil,” which Joyce wrote for his grandson Stephen (aged 4), can be traced back to the first of these visits. Respectful to the original letter, with only a minor amount of editing, “The Cat and the Devil” is, as Joyce’s grandson himself would later attest, a wonderful story told through straightforward language — the language that any three or four year old child could understand.

(See McSharry, Katherine, “Stephen Joyce , the boy who became guardian of his grandfather’s legacy,” The Irish Times, Sat Feb 08 2020.)

While it is true that Joyce relays the story in a straightforward grandfatherly tone, it is made clear through the end of this letter to “Stevie” that he could not resist the playfulness and self-reference for which he had become famously known.

(FYI: Joyce’s original letter to “Stevie” can be found in Stuart Gilbert’s 1964 volume, Letters of James Joyce. We Too Were Children has more images, a synopsis and a timeline of different editions of “The Cat and the Devil”.)

P.S. The devil mostly speaks a language of his own called Bellsybabble which he makes up himself as he goes along but when he is very angry he can speak quite bad French very well though some who have heard him say he has a strong Dublin accent.

—James Joyce, The Cat and the Devil

With respect to Joyce having eminently enjoyed playing the diabolical role, even in his childhood , his brother, Stanislaus, later remarked “[t]hat he had [always had] an instinctive realisation of the fact that the most important part, dramatically, was that of the Tempter” (Quoted in Carey, Gabrielle, James Joyce A Life [Melbourne and Galway: Arden, 2023], 3.) We plan to shed further light on this comment through the ensuing series of posts here at ISI Dublin exploring James Joyce’s influences.